Clockwork Utopia

When Huxley wrote Brave New World he was only guessing at some of the things we have in store for us. He was the grandson of Thomas Huxley, Darwin's "Bulldog," and his own literary career featured pointed social criticism. None of it was more pointed than when he wrote BNW, which argued that we were gaining the tools to make ourselves truly miserable. Aside from global warming, we now read about farmers whose corn crops are ruined because gene-mod pollen from miles away crossed into their field. Super weeds are creating a headache that only promises to get worse. Drug resistant bacteria threaten medical practice.

There are always the cheerleaders, of course. For every opponent of globalization, for every critic of gene-mod foods and other modern miracles, there are the cheerleaders. We couldn't feed ourselves without gene-mod foods, they argue. Modern medicine is extending life expectancies to the century mark. Economies work best when every economy is allowed to find the things it does best and concentrates on them. These voices argue against regulation, against oversight, for innovation.

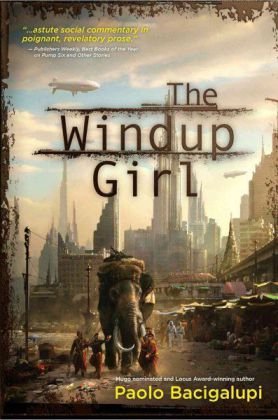

So when Paolo Bacigalupi writes about a future that makes Huxley's story seem like a nice place to visit, it's not altogether implausible. In The Windup Girl we find ourselves in Bangkok, in Thailand. The oceans have risen, as expected, and the only thing keeping Bangkok from drowning is a seawall and a number of gigantic pumps. Nations pay a carbon tax for the fuels they burn, and Thai manufacturing now relies on the muscles of gargantuan genemod derivations of elephants and horses. The city's proud skyscrapers stand mostly empty, with no cheap electricity to run elevators or pump water to their tops. A genocide of ethnic Chinese in Malaya has sent streams of refugees into Bangkok where they squat in the slums, hoping that the horrors from Malaya don't follow them there.

We meet a number of disconnected people. An agent for an American corporation which is apparently guilty of crimes against humanity that dwarf the Holocaust. A police officer whose moral fiber is unusual for this incarnation of Bangkok. And the book's namesake, a Japanese genemod woman, discarded from a rich man's entourage to suffer torture and rape in a prostitution parlor. (No, this book is not recommended for young readers or sensitive dispositions.)

Bacigalupi proceeds to tell quite the spellbinding story. Mysteries arise, outrages are committed, a civil war ignites. Through it all the windup girl suffers, serving as a kind of mirror, an avatar for the suffering Earth. It is mostly an excellent book.

I did notice that towards the end the story editing got sloppy. There were continuity problems, and it wasn't always clear what was happening when. Why stuff like that makes it past the editing, I don't know. An otherwise excellent story like this certainly deserves closer attention to detail.

Anyway, another great entry for the 2010 Hugos.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home